I recently watched “The Glenn Miller Story” for

probably the 19th time. Hollywood took significant liberties in bringing

the story of band leader and arranger Glenn Miller to the big screen. According

to his former band members, the real Glenn was not nearly as charming as Jimmy

Stewart, who played him in the movie. But I love the part where Glenn (Jimmy)

tries to describe the drive to create something new, to combine instruments in

a way no one has done before, and achieve a unified sound from the variety of

instruments and musicians playing them. I have this arranging bug. I’m not

happy unless I am arranging something: a tune for a saxophone quartet, a full

big band score, or a duet for two flutes.

When jazz started out it was mostly a small group

affair, with instrumentalists making up their parts and predominantly playing

by ear. As bands grew larger, this improvisatory approach became untenable, and

the role of the arranger increased in importance. All the great band leaders depended

on arrangers. As skilled as they were, many remained in obscurity, known only

to fellow musicians or the most ardent fans.

Arranging work can encompass a wide variety of

situations, from writing a “chart” for the Count Basie Orchestra, to scoring the

strings and brass for a furniture commercial. Almost every piece of music we

hear that involves more than a four-piece band requires input from an arranger.

Most arrangers played an instrument and often paid their dues as sidemen in

traveling bands. Pianist Mike Abene experienced the typical road travails and

additional instrument hassles that helped push him down the arranger’s path:

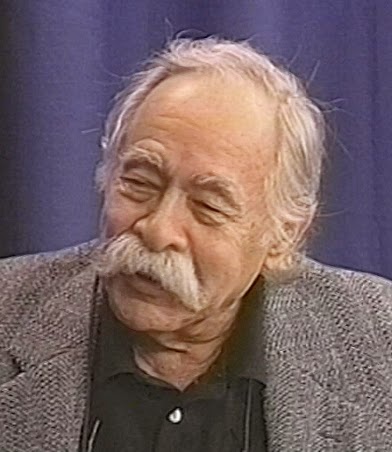

|

| Michael Abene |

MR: What

was the road like at that time?

MA: My

big thing on the road was with Maynard [Ferguson]’s band. You know I didn’t go

through a lot of bands because I was so involved in the writing end of it. But

with Maynard at the time it was funny. It was like two station wagons and a

panel truck. And you’d have like basically — and it was a smaller band, it was

like four reeds, two trombones, four trumpets including Maynard, and three

rhythm. So you’d have usually the band boy and one driver would be driving the

panel truck and the rest of us would be split up into two station wagons.

Which, if you’ve ever ridden with five or six guys in a station wagon, six or eight

hundred miles, it’s not — so to this day I can sleep bolt upright — in a train

or car I can just sit bolt upright. It looks like I’m looking at you and I

could be asleep. But the thing is, it was funny with Maynard because I was

never really happy with any of the records first of all. And just the recording

quality, it was only one record I felt that the band really sounded good was a

thing called the “Blues Roar.” And we had enlarged the band at that, for that

particular — it’s Don Sebesky and I and Willie Maiden did the writing. But in

the clubs, when we’d do clubs or concerts, it was wonderful because Maynard

would just open up all the charts and we’d play like it was a small band. It

would just, I mean some tunes were like 45 minutes, 50 minutes, and the rhythm

section just used to be very loose. So if we could only capture that on record

I always felt. But I mean generally it was a good experience in that Maynard

was a very good band leader, sometimes a little too lenient you know, but he

was a great guy. I have no complaints about that. A lot of good things

happened.

MR: As

a piano player, did you ever have to deal with lousy pianos?

MA: God,

that’s why I prefer writing. You just answered — and you just solved the riddle

of my life. People say don’t you miss playing. Yeah I miss playing. But I

really love writing because, the first reason being that you know you guys can

play your own horns, like the drummer plays his drums, the bass player, but

then you’re stuck with some of these pianos, they’re just hideous. And to this

day that’s still kind of an occupational hazard for piano players too. But

that’s why, and the other thing is sometimes you play and you play a great

solo, right? So the next night you go back and nobody even has any idea about

how well you might have played the night before. It’s up in the air someplace.

At least you write something, a good band, it’s there to remind you if it’s

really good.

In all the interviews we’ve gathered for the Fillius

Jazz Archive, I have never once spoken to a successful musician who was forced

into the business. Mike Abene confirms that the path of a musician/arranger has

to be self-motivated.

MR: When

you were a teenager, did you have a choice in your career or were you compelled

to just go into music?

MA: I

was compelled, not through my parents, but self-compelled. And I realized very

young that I really wanted to be in music. And my whole family was basically in

music. My father was very good, like a Freddie Green kind of guitar player. He

had a big band, and his brothers all played. It was the Italian end so they

were all barbers and string players or [they played] accordions. His father was

an accordion player and mandolin and everything. And my mother’s side of the

family, her brothers, you know one brother was a drummer, another brother sang,

he married a woman who was a hell of a pianist, couldn’t read a note of music

but was one of those could hear something once and retentive, just bang, could

play it. So it was always around. But I really enjoyed — I was actually writing

and playing professionally at 15.

Manny Albam has arranged for an impressive list of

artists including Gerry Mulligan, Carmen McRae and Count Basie. As a saxophone

player, he avoided the instrument woes that Mike Abene had, and his physical location

in the band had an impact on his fledgling arranging career.

|

| Manny Albam |

MR: Why

the saxophone as your instrument?

MA: It

started as the clarinet. I think I was about 13 or 14 and I guess I was

mesmerized by Goodman and Shaw. And Pee Wee Russell. Pee Wee was actually more

of a hero of mine than the other two guys, they were a little too glib and

smooth and all that. But Pee Wee had that essence of jazz. The rough tone and

the whole thing.

MR: His

personality was kind of interesting to watch too.

MA: Oh

yeah. I finally met him in Boston, we stayed at the same hotel and I ran into

him in the lobby and we talked a little bit. As a clarinet player I was almost

forced to take up the alto. And I started sitting into a lot of bands as a

second alto player. Now the second alto chair in those days, in the four-man

sax section was also baritone chair and so I became a baritone player and I’m

glad of it. I finally sold my alto. As a writer from the baritone chair you

hear everything up above you. You hear from your position way up to the first

trumpet and you hear right through all the chords and the voicings and all of

that. It’s a great place to live. And conversely, a lot of the arrangers, they

were trombone players and they sit right in the middle and they hear it from

both sides I guess. That’s where their thing is. You know, Brookmeyer, Billy

Byers, Ray Wright, a whole bunch of them, Don Sebesky, for some reason or

other, Nelson Riddle was a trombone player. It seems to be those two chairs are

great places to hear what other people do. So if you play other people’s

arrangements, you can learn a lot from them.

Like most arrangers, Manny Albam had to deal with a

rapidly changing music scene. His career spanned the swing era into rock &

roll and commercial work. Swing bands, and especially studio players, were

required to be excellent sight readers. Manny didn’t realize he had become

spoiled over the years by working with musicians who could play his

arrangements correctly, usually the first time. He had a rude awakening when he

started writing for rock groups.

MR: Did

it change your work at all when rock & roll became the popular music?

MA: Well

what happened to me a couple of times, there used to be a group in Canada

called the Guess Who, and there was another one called the Lloyds of London.

They would come down to New York and cut a basic track and then I would go in

and add strings and horns and whatever. And that began to become like a joke.

They’d go in, first the bass player would come in and play his line. And then

the guitar player came in and says, “wait a minute I can’t play with that

thing, you’ve got G natural and it’s wrong – I can’t do that.” So the bass

player would have to make another track. And then the piano player came in and

they’d change. So to get one thing down sometimes took three or four days.

Finally they got two tracks down and I took them home and I would write

“sweetening” is what they’d call it — strings and horns and all that. And we’d

call the session and the string players came in and sat down and they played

the thing through once and we recorded them the second time and they left and

then the horn players came in. And these guys were, “holy Jesus, you mean you

did the whole thing in 20 minutes? I can’t believe it.” I said, “well they’re

musicians. They read music.” You’d have like Marvin Stamm or Bill Watrous or

whatever. They’d just come in, sit down and go [scats] and leave, and pick up

their $90 or whatever. And the [rock] groups didn’t know then who they were

dealing with yet. They were dealing with great players.

Part of being a successful arranger is recognizing

what is needed for a particular artist. Bill Holman, who was capable of writing

thick and powerful charts for Stan Kenton, intuitively recognized the need for

space when he had his first assignment for a vocalist:

|

| Bill Holman |

MR: You

had quite a list of singers here that you arranged for also. When was your

first experience doing a chart for a singer?

BH: It

must have been around the middle 50’s for Peggy Lee. I believe in starting at

the top you know. And I was really scared because I had kind of a crush on her

since 1942.

MR: Oh

that’s nice.

BH: But

she’s a great singer, so I really took it easy writing the charts. I didn’t put

a whole lot in there, you know, afraid to get in their way. She told me later

after a couple of years, she said, “the thing I really like about your charts

is all the stuff you leave out.” So I guessed right on that one.

Sometimes the biggest challenge in a “work for hire”

arranging assignment is the quality of the original content. During my

arranging/studio experience, the engineer had a phrase we used when we were

trying to rescue music that had no redeeming qualities: “putting frosting on a

turd.” Bill spoke honestly about his brief film scoring career:

BH: I’ve

never gone into actually composing for movies. I did a couple of grade C movies

in the ‘50’s.

MR: Did

you ever see them?

BH: Yes.

One of them made T.V. and it comes out occasionally as a re-run. It was called

“Swamp Women.”

MR: “Swamp

Women” with score by Bill Holman. Yeah?

BH: Yeah.

Terrible music.

MR: I’m

going to watch it.

Maria Schneider is one of the more recent arranging

success stories, and like Duke Ellington, found it a necessity to have her own

group to play her music. She is articulate and thoughtful in her teaching and

passing on what she has learned:

|

| Maria Schneider |

MR: How

do you impart some of your

philosophies to other students? Is it possible to do that?

MS: I

try to just show them how I dance around and try to figure my way into music. I

try to encourage students to look for something that just feels good, then try

to find the logic in it, keep developing the logic, but kind of let their left

and right brain work together so that it doesn’t become too analytical. And

never thinking what do they think I should write, what’s going to be hip. What

should I adopt to be cool. But try to stay inside. I always feel like the thing

that makes each person unique is that you are you, nobody on earth can imitate

you, nobody can be more you than you are. So that your job is to become you to

the deepest degree that you can, and that’s where your beauty and that’s where

your mastery is, in developing yourself. I think so often it’s really easy to

look at other people and say oh he’s a master, I have to try to be like that, I

have to follow him. No, you have to find the depth of yourself and be

disciplined and develop yourself to the same degree that those people were

disciplined and developed themselves. And that’s the thing that nobody can

imitate. And that’s where your strength, and that’s where your gift is. That’s

what people want to see, is feel the uniqueness of each other. That’s where you

really communicate something fresh with somebody. It’s hard to do that.

Maria also believes that an artist cannot live in a

vacuum, that their work must be inspired by circumstances that come from living

a full and active life.

MS: Music

isn’t enough for me in life. There’s other things too. And I love music but I

think what I love about music is it’s a valve for other things. I love life,

and I want more time to live. And to me music is, one of the problems with

musicians is I think they get so caught up in making records and going to the

next project that very often the person’s first record is the most powerful.

Because that record represents years of just working on your own and doing

other things in life, and then suddenly you become so busy doing your music you

aren’t paying attention so much to the other things in your life because they

aren’t as important as the music. But what feeds the music? Music is fed by a

deep and rich life. So I think it’s really important to have other things in

your life that you can do with equal love.

Even with computer programs that enable arrangers and

composers to hear their work as it’s written, there is nothing like that first

“human read-through,” real musicians playing your work. It’s a challenge to

conduct with your fingers crossed.

My next entry will highlight some magnificent

arrangements from different musical genres.